Very early in my career, I was on a phone interview for a product management role. I thought it was going well overall – we had a good rapport, I highlighted some achievements I was proud of and even gave them some ideas for their business I had uncovered in my research. Then came a no-brainer question that I was ready to knock out of the park.

Can you describe a product or experience you love, and why you love it?

Just one product? Easy! I have dozens. I live for technology. I make it a habit to see every new consumer product, every new programming framework, every new blog post I can find to add to my internal map of the digital world.

But I blew it. Not at first, though. Describing why I loved this product was easy. I articulated my points clearly and considered the broader applications and lessons. Then the interviewer asked a simple follow-up.

What did they get wrong?

I hesitated for a second, as I really was enamored with this product at the time. Then I remembered a bug that kept creeping up. It was a relatively small thing, a minor annoyance, but it happened frequently. So I described it, and a basic overview of how they could fix it. Great - not only a problem but a potential solution. Another follow-up from the interviewer:

So why do you think they haven’t fixed it yet?

I hestitated again, then I answered:

Well, I guess they might not have really noticed it, or weren’t exactly sure how to fix it.

I lost the job with that answer.

How could I assume that the company that was building this product, a company known to sweat design details to the nth degree, wouldn’t have noticed this bug? Or that I was somehow so uniquely positioned to know how to fix the issue when they couldn’t?

Obviously it was a terrible assumption.1 Most likely, it was on their backlog of fixes but they had to cut it from the release. It was too costly or would take too long to fit into the current iteration, and was simply prioritized appropriately for the future.

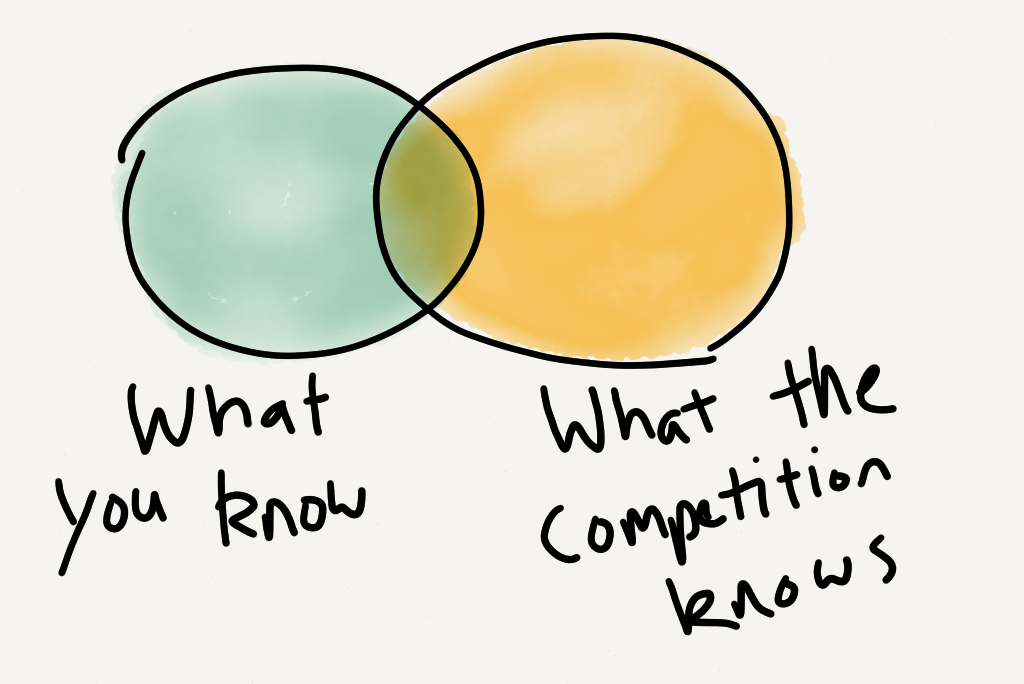

But you see these types of bad assumptions come up in conversations all the time. As a culture, we are quick to assume that we know more than others, that they don’t “get it”. We believe that if they only knew what you know, they’d agree with you. Of course this is folly - it’s a form of attribution bias. Two quick examples that come to mind:

- HBO is leaving money on the table because they don’t offer HBO Go to people without a cable subscription.

- A company with no pricing listed, no self-signup or self-service checkout is leaving money on the table from people who don’t want the hassle of calling in and dealing with a sales team.

For both of these scenarios, the error is only considering the upside of a different decision and not the costs. Here’s what I said recently on Hacker News about the HBO situation:

It’s really not safe to assume that media companies “leave a lot of money on the table” by not catering to cord cutters. Cord cutters are currently a very small market, and HBO would lose a lot of leverage over the cable companies. At the margin they’d rather have 1 cable subscription over 1 stand-alone subscription - or even two or three for that matter.

The bear case is actually the opposite - they aren’t leaving any money on the table now, but it will be at the expense of future growth. They’d be better cutting over to stand-alone sooner, at a loss in current revenue, to better position themselves for the future. That may or may not be the right play, but that’s really how you should be reading the current market.

Giant companies are often not very customer-friendly, but they are rarely leaving obvious money on the table.

And what about the aversion to sales teams? Another anecdote comes to mind.

There’s a very smart company I know that resells complex products like insurance. They’re better at selling these products than anyone else in the industry.2 They don’t offer any self-service options; every sale is over the phone. They built a huge in-house call center and spend a lot of money to keep it running. But don’t assume they could cut costs and increase revenue by moving things to a self-service model. Because they’ve tried. They test everything, rigorously and methodically, and they’ve found time and again that forcing a call is the best thing for them. They may get fewer overall leads, but they have higher-qualified leads, and overall, they convert more people to paying customers.

These are just two examples, but as a concept it’s something you need to be very conscientious of.

Don’t assume the worst out of a market, or a competitor. Don’t assume they’re missing some key insight or piece of information. Work hard to understand why things are the way they are. Maybe they are missing something crucial that you can ride all the way to the bank. But more often, you’re actually the one that’s missing the information. If you can’t cop to that, someone else is going to eat your lunch.

-

For my own sanity, I chalk up that answer to the inherent pressure of an interview – I simply choked. ↩

-

I don’t have hard data on this - its an assumption! But it’s an assumption based on their size as a reseller. They wouldn’t reach the scale they’ve reached if the companies producing the products could sell as well as they could. ↩